This article walks through an approach to convert an unstructured address into a structured (or hybrid) address complying with the ISO 20022 PostalAddress24 (CBPR+) ready for November 2026. The code to do this is available in the Github repository. It is a python project using Libpostal. If you need support installing and configuring Libpostal and the Senzing model on Windows, see this article.

Should you need specific help, please do contact me.

All addresses used in this article are random examples found from publicly available sources.

Overview

Addresses are tricky things. Simple enough to understand, ubiquitous in payments, whether needed or not, yet devilishly difficult to standardise.

In the payments domain there are addresses for your own customers (debtors), for their beneficiaries (creditors), ultimate parties (at either end of the payment chain), and any banks involved.

Addresses are tricky things. Simple enough to understand, ubiquitous in payments, whether needed or not, yet devilishly difficult to standardise.

In the payments domain there are addresses for your own customers (debtors), for their beneficiaries (creditors), ultimate parties (at either end of the payment chain), and any banks involved.

It is this combination of prevalence and non-standardisation that makes the switch to the ISO 20022 structured format[i] particularly challenging. Since you are reading this, it is a challenge you may well be aware of and yet to solve. If you have not started, I encourage you to do so.

Amid the current AI frenzy, many will be thinking about the utility of AI, specifically LLMs or generative AI, as the solution to convert addresses. In this article, I dare to suggest that LLMs are not the solution though could be considered as a last resort. There are other, simpler, faster solutions that can be utilised whether in bulk, on large address datasets, or individual addresses per transaction. Libpostal is one such first-choice solution which, when combined with other techniques, can be particularly effective, removing or certainly minimising the need for an LLM. It is this we will explore here.

The Unstructured Address and Data Quality

Even the smallest of corporates, banks and PSPs, will likely have screens, channels, interfaces and persisted data stores that were built on the unstructured address or the “123 address” as I’ll refer to it; that is a format usually of address line 1, 2 and 3, often 4. The address elements populated in these lines will vary and there is often no consistent data mask applied. This is the unstructured address challenge, likely made more challenging through inadequate quality control on the data input – spelling mistakes, unconventional sequencing of address elements, scant data, nonsense data, locales and the variations symptomatic of free-text data entry. Take my country – free-text would allow the user’s choice which could be any one of GB, G.B., UK, U.K, England, Great Britain, United Kingdom, The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and on…).

Before we delve into methods and strategies for converting unstructured addresses, be mindful that the accuracy will depend, more than anything else, on the quality of the source address data. A structured address must have both a Town Name and Country. The same applies for a hybrid address (do not be fooled, this hybrid option does not help us[ii]), so if the source address is missing either, you have a choice to make – a technical solution to fix or remediate at source. Let me help in that decision…The technical solutions I will be discussing are not a prescription for treating poor data quality. They will expose the flaws and where you see hot spots of failed conversions, invariably the issue will be the data quality. Report failures back to the data owners to fix at source. Fixing at source, through data remediation and input controls will be far more cost-effective than attempting to fix in your address converter. Lest we forget, ISO 20022 is about data, data, data.

Different Gravy

We will focus on the 123/unstructured address – the worst case – but you may be blessed with different gravy (Google it!). Your cohort of addresses may be of higher quality with a more granular structure, a specific country field, possibly a city field. Even from this better starting position, the methods here – Libpostal and geocoders – may still prove useful, so do read on.

The Approach

Everything described in the following approach is available as working Python code from Github. If you are looking for a Java implementation, almost everything described here, and the Python code can be refactored in Java.

As will quickly be apparent, this article will be somewhat technical, albeit simplified. It is not a theoretical white paper. The code and approach provide a template you can clone and adapt to suit your gravy. It is this code that I will walkthrough.

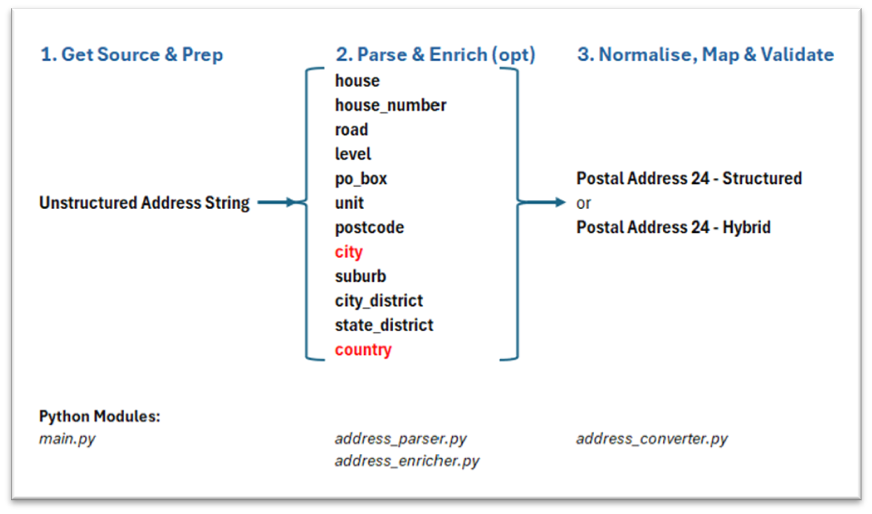

So, the approach is to utilise Libpostal and optionally a geocoder (which could be an AI service), to convert the unstructured address to a valid Postal Address 24 structured format. If the structured format is not possible, a valid hybrid address format. To achieve this, we will follow these three stages:

These stages are akin to those in a trading application. A trading bot has standard, static functions – connecting to an exchange, logging, getting and normalising historical data, getting market data, setting limits, executing a trade, updating positions, calculating balances and P&L etc. You also have the pluggable decision-making strategies which trigger a trade. These are highly dynamic (and certainly for those I have built, unprofitable) strategies. They are constantly retuned, optimised and swapped in or out of the trading bot based on your back-testing and real-time P&L.

In our address conversion journey, Stages 1 and 3 are the standard static, rules-based functions – preparing the data and later, normalising and mapping parsed elements from the canonical model to the structured format and integration into our payment messages.

Stage 2 is the pluggable, dynamic “conversion strategy(ies)”. Source data quality aside, the sophistication of your conversion strategy(ies) will dictate the quality of your parsed address. I am providing one basic conversion strategy in this code. You can adapt and build others from this.

For those organisations professing to be agile but still in a waterfall mindset with waterfall governance, this address conversion challenge offers the opportunity for both methodologies. Stages 1 and 3 can all be waterfall, but Stage 2 must be agile – rapidly designing, building and trialling differing conversion strategies against real datasets requires agility. The goal of a 2-week sprint could well be the design, build, execution and review of at least 2 or 3 different strategies.

Stage 1. Get Source Data and Preparation

Python file: main.py

This is the orchestrator. It collects the input parameters including the address(es), iteratively passes each address to Stage 2, receives its response which it then passes to Stage 3 for the output.

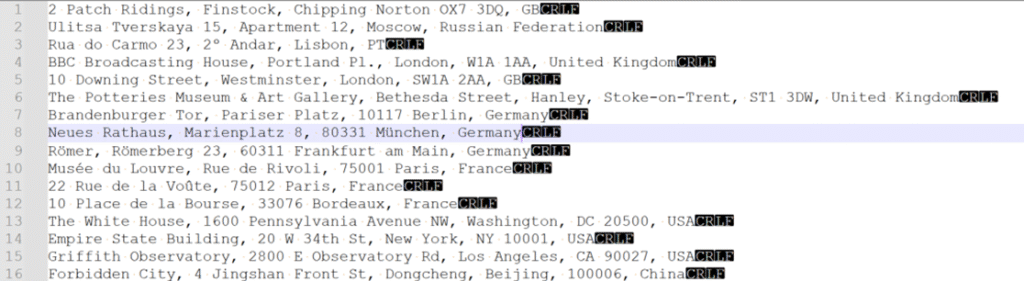

We start by reading a text file of one or more addresses into the application. Your own analysis and design will need to determine your data sources, whether persisted or on-the-fly, the formats, conventions, method(s) to call them etc. In our code, we will accept a text file of multiple lines, one address string per line, such as:

This stage does little else but does capture the parameters needed for the following stages. Console inputs are used to capture these parameters:

- Enter Text file path: the location of your text file of addresses, e.g. “C:\your_path\your_source_addresses.txt”

- Enter Output folder: the folder to save the results of the conversion. This is a csv file with the xml address plus metadata, e.g. “C:\your_path_to_save_the_converted_address_results”

- Available address types: 1. UNSTRUCTURED (unstructured): Choose your strategy/address type. The code only has a class for the unstructured address so will be the only option. This is a parameter only for future extensions – you can build more classes for differing source address types each of which can be customised as required, such as for military addresses, Care of, PO Box addresses, specific country formats etc.

- Enter starting row number in file (default 1): in case your text file has a header row, then start on row 2.

- Allow hybrid address output? (y/N): Choose whether to allow a hybrid address. By default, the conversion will attempt to produce a structured address, truncating any excess data to fit the field. If hybrid is allowed, any field that would otherwise be truncated, is moved to the Address Line(s), hence it will be a hybrid. The hybrid address format has a limited lifespan and although Swift has not announced an end date, when it does, this parameter allows for quick disabling of the hybrid option, without any code changes. If disallowed, the structured address may have truncated data. We will discuss this in more detail in stage 3.

- Allow geo-enrichment if Town Name or Country missing? (y/N): both structured and hybrid addresses must contain the Town Name and Country to be valid. In cases where the source address is missing either of these or it cannot be fixed at source, this parameter, if enabled, will attempt to enrich the missing elements. We will also discuss this in more detail in stage 2.

Stage 2. Parse and Optionally Enrich

Python file (address_parser.py, which calls address_enricher.py)

Agility is needed here as this stage does the heavy lifting and requires repeated trialling and refinement. It prepares the address for parsing by Libpostal then actually parses it. Based on whether the parsed result contains a country and town/city element and whether geo-enrichment is permitted, it may then be enriched. Geo-enrichment in this code uses an open-source geocoder, Nominatim. More on that later.

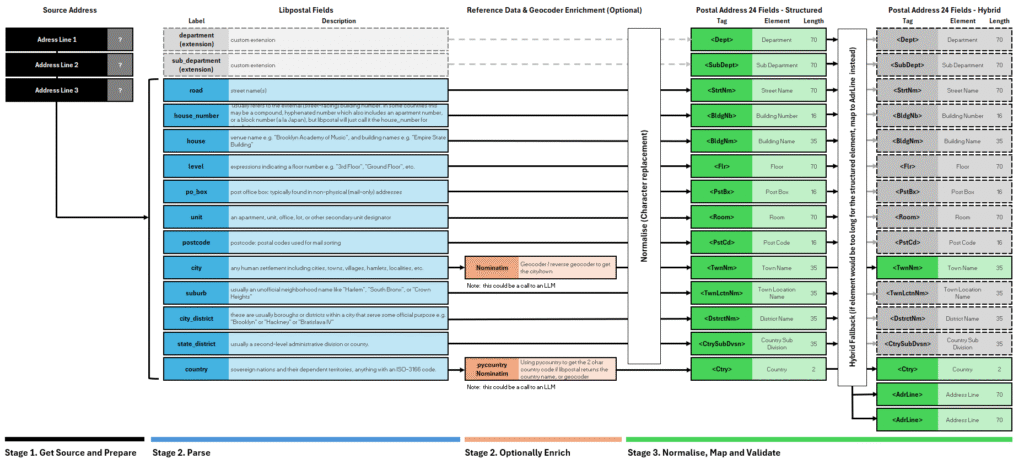

We are always using the Libpostal labels as our canonical model. This becomes important when multiple conversion strategies are used – if they all use this same model, regardless of whether Libpostal is used, the mapping in Stage 3 is static and reusable.

Parse the Address

Python file: address_parser.py

For the parsing section of this stage, there are three steps:

- Parse the Address (parse_address). This is the main function, which passes the address into the Libpostal parse function and receives the result. It then calls address_enricher.py to check the result for correction and possibly enrichment. Before this though, it calls pre-libpostal and post-libpostal functions, as follows.

- Pre-Libpostal (_prepare_for_libpostal). This step prepares the address string to achieve the best chance of success for Libpostal parsing. In my code it does little as we are working with a single address field, with no indication of how it is formatted. We will discuss rules-based parsers later, but these could be implemented here. For example, if you know that your addresses always end with a 2-character country code, you could parse this out here, ready to pass as a distinct country parameter to Libpostal. You could go further. Assuming you then have a country code, you could attempt to parse out, say using pattern matching/regex, the postcode. Once you have individual address fields, you can then recompose the address string in the order usually used for the given country. This function is far more important if you have semi-structured addresses as re-ordering of known elements becomes much easier. Passing an address that has elements in the order expected of the given country will improve the accuracy of Libpostal’s parsing. It is after all, specifically trained on addresses conforming to these country conventions.

- Post-Libpostal (_optimise_libpostal_components). The Libpostal result is a list of the parsed address fields and because it is a list (not a dictionary), there may be duplicate items. For example, ‘road’ may appear twice, each with different values. This function is designed to rationalise and optimise the list. It is simplistic, assessing the most complete item to be the longest, which it then selects, ignoring the other. You could implement far more sophisticated optimisations to suit.

Stage 2 uses parsers both rules-based and Libpostal. It also, optionally, uses geocoders. The distinction is important.

Parsers

Simply, a parser takes only the supplied address and breaks it into what it determines to be the individual address components. It labels these items. Different parsers usually have their own syntax (labels) – city in one parser may be town in another[iii].

Importantly a parser does not enrich the address. If you input an address without a city, the result, however the components are parsed and labelled, will not contain a city. It may incorrectly label one part of the address as the city, but it will be a part that was present in the input.

Some parsers operate on “old-fashioned” rules-based logic, such as searching the address for text matching a particular postcode pattern. These are cumbersome, slow and often need clean source addresses and only from specific geographies. They alone are unsuited to converting unstructured addresses but can be useful when applied to an already parsed address element or to prepare an address for Libpostal if it follows a consistent, known format. Parsers and be third party applications but more commonly, in-house development and often simple functions. Parsing may require multiple passes, and conditional logic checks all of which has a performance impact so should be used prudently.

Libpostal

Libpostal is a parser, though not the old-fashioned rules-based type. It is an open-source statistical natural language processing parser (NLP). It uses machine learning to provide structured predictions based on a large dataset of real addresses, international by design, in different languages and locales. This pre-trained model is all wrapped in a self-contained lightweight package written in C and available in various bindings, Python, Java etc.

Libpostal is ideally suited to parsing unstructured addresses. Additionally, because it is trained on various languages and locales, it will expand on the original source address, by way of normalisation. This is not the enrichment that geocoders offer. For example, High St. may be parsed and labelled as the ‘road’ element, but the value itself may be expanded to High Street. Similarly, Ave. to Avenue etc. At times, this normalisation is helpful, at other times it can be problematic.

Libpostal has two primary functions (in the python binding):

Address Parsing (parse_address)

This is the function we will use most. Using a python example:

For source address:

BBC Broadcasting House, Portland Pl., London, W1A 1AA, United KingdomCalling:

parse_address("BBC Broadcasting House, Portland Pl., London, W1A 1AA, United Kingdom")Will return a labelled list of address components as follows:

[('bbc broadcasting house', 'house'), ('portland pl.', 'road'), ('london', 'city'), ('w1a 1aa', 'postcode'), ('united kingdom', 'country')]We can then further process these elements, if necessary, before mapping them to our PostalAddress24 format.

parse_address takes two other optional parameters[iv] in addition to the address itself.

- language: such as ‘en’. Informing libpostal the locale of the address being parsed.

- country: such as BE. Informing libpostal of the country code of the address being parsed.

Both optional parameters should be used if possible as they will improve the result. Unfortunately, to pass these parameters, you may well need to have parsed them out of the address in the first place; catch 22. Though, if your source addresses do have a separate country field, then always use this to pass into the parse_address function. Likewise, if your source addresses always have a country code in a certain position, say as the last two chars, this could be extracted using a rules-based parser. It is the adaptation and optimisation of this basic strategy that you will need to apply to get the best results.

Address Expansion (expand_address)

This function is normally used when the structure of the input is vague or uncertain and all variations of the address may be needed to present back to a user so they can choose the most appropriate. For example:

Using the same source address and calling:

expand_address("BBC Broadcasting House, Portland Pl., London, W1A 1AA, United Kingdom")Will return a list of expanded address variations:

['bbc broadcasting house portland plain london w1a 1aa united kingdom',

'bbc broadcasting house portland place london w1a 1aa united kingdom',

'bbc broadcasting house portland plain london w1a 1 aa united kingdom',

'bbc broadcasting house portland place london w1a 1 aa united kingdom',

'bbc broadcasting house portland plain london w 1a 1aa united kingdom',

'bbc broadcasting house portland plain london west 1a 1aa united kingdom',

'bbc broadcasting house portland place london w 1a 1aa united kingdom',

'bbc broadcasting house portland place london west 1a 1aa united kingdom',

'bbc broadcasting house portland plain london w 1a 1 aa united kingdom',

…]Address expansion should be used judiciously. As you can see, many variations can be returned. Most are unhelpful and the normalisation issue may be present. In this case, Pl. has been normalised to Plain in some variations. This often occurs with St. being normalised to Saint rather than Street.

If parse_address does not produce a good enough result, it is possible to chain together these two functions. First use expand_address, from the list, select the best variation and then feed this back into the parse_address function. There is one small issue with this. How do you systematically know which of the expanded addresses is the best one? You do not.

expand_address whilst useful when presenting the results back to a user for their selection, is not useful in our scenario. My code does not use it and relies only on the parse_address function.

Libpostal does struggle with certain geographies, such as those that do not follow the Western convention of building number, street, town, postcode, country, however many of the alternatives struggle too. Middle Eastern addresses can be particularly challenging, one of the reasons for the advent and expanding use in other industries of Google Plus Codes and What 3 Words – in the future we may see the acceptance of these in ISO 20022, possibly as part of digital identities.

Another problematic area are addresses that include elements such as department. Libpostal syntax does not have a direct label, something I consider in Stage 3. In many cases the less data in the source address, the better. As you start to parse your addresses, you come across these and other issues. This is very much a test, fix at source, optimise and repeat process and when working on large address datasets can be extremely time intensive.

Enrich the Address

Python file: address_enricher.py

Once the result of the Libpostal parsing has been optimised, this address dictionary (not a list anymore) is passed for enrichment. Irrespective of whether you allow_geo_enrichment, it will always geo-correct if necessary

Geo-correction may be needed if the dictionary has a country name instead of the country code, for example. Geo-enrichment if the dictionary is missing either the city or country.

Geo-enrichment is complex and discussed in the next section on Geocoders.

The main function, enrich_address, will return the address in a dictionary of updated elements called best_address_components along with a flag to indicate if the city was enriched and if the country was enriched.

Before we move on to stage 3, having talked about parsers and Libpostal we should cover geocoders.

Geocoders

Geocoders are also parsers, but unlike rules-based parsers or Libpostal, they use external open-source or proprietary geodata repositories to identify the address passed to it and return all components. This may include much more than town and country, such as political boundaries and administrative divisions.

Using a variation of the BBC address from earlier but now missing the city/town name (London):

BBC Broadcasting House, Portland Place, W1A 1AA, United KingdomLibpostal will parse this address adding the following labels. It cannot enrich with the correct city:

[('bbc broadcasting house', 'house'), ('portland place', 'road'), ('w1a 1aa', 'postcode'), ('united kingdom', 'country')]We cannot use this to generate a syntactically valid PostalAddress24 – the Town Name being mandatory.

Using the geocoder, Nominatim in this case, the address is parsed with the following labels and enriched with additional data – neighbourhood, city, district_county, state_province, and the country_code. Note that Nominatim returns the address in its own syntax (e.g. street_name rather than road). In Stage 3 we will use Libpostal syntax as the canonical model, so anything returned from your chosen geocoder, needs to be aligned to this model:

{'building': 'BBC Broadcasting House', 'house_number': None, 'street_name': 'Portland Place', 'neighborhood': 'Fitzrovia', 'city': 'London', 'district_county': 'Greater London', 'state_province': 'England', 'postal_code': 'W1A 1AA', 'country_code': 'GB', 'country_name': 'United Kingdom'}Now we have all the address components to generate a valid PostalAddress24 – we have the city which we will map to the TownName.

If Nominatim could not find this address, we can also fallback on reverse geo-coding. This attempts to generate latitude and longitude coordinates from the address and then, based on the scale/zoom level, determine the country and nearest urban centre in an ascending order – such as hamlet, village, suburb, town, city, municipality, county etc.

Nominatim geocoder and reverse-geocoder are both used in the code.

I would argue that an LLM is another geocoder and as you can see from the BBC address example, they work. Geocoders have drawbacks though. They are external services to be called. This has security, data privacy and specifically performance implications. There is also the cost. Whilst my code uses Nominatim, which is free, it is rate limited and not suitable for a high volume, critical production payments system. Many others are available, for example:

- Google Geocoder (pricing plan – free tier less than 10,000 calls / month)

- HERE (pricing plan – free tier less than 30,000 calls / month)

Each gives different results and uses different syntax, so testing is vital. For example, for the address below, which after parsing with libpostal did not produce a city (should be Fnaitees), Nominatim, Google and HERE gave the following results:

244 Abdulaziz Bin Abdulrahman Al Saud Expy, Fnaitees, KuwaitWe are aiming for “Fnaitees” to be parsed as the TownName/City by the geocoder.

- Nominatim: No address found

- Google Geocoder: parsed “Fnaitees” as the locality (equivalent to TownName)

"address_components": [{ "long_name": "244", "short_name": "244", "types": ["street_number"]}, {"long_name": "Abdulaziz Bin Abdulrahman Al Saud Expressway", "short_name": "Abdulaziz Bin Abdulrahman Al Saud Expy", "types": ["route"]}, {"long_name":"Fnaitees","short_name": "Fnaitees", "types": ["locality","political"]},{"long_name": "Mubarak Al-Kabeer Governorate","short_name": "Mubarak Al-Kabeer Governorate","types": ["administrative_area_level_1","political"]}, {"long_name":"Kuwait","short_name": "KW","types": ["country","political"]}],- HERE: parsed “Mubarak Al Kabeer” as the city which is the governate of Fnaitees but Fnaitees itself has been dropped from the parsed address. Also note the address itself was changed from 244 to 241, not sure why!

"resultType": "houseNumber","houseNumberType": "PA","address": {"label": "Abdulaziz Bin Abdulrahman Al Saud Expressway 241, Abu Hasaniya Mubarak Al Kabeer, Kuwait","countryCode": "KWT","countryName": "Kuwait","county": "Mubarak Al Kabeer","city": "Mubarak Al Kabeer","district": "Abu Hasaniya","street": "Abdulaziz Bin Abdulrahman Al Saud Expressway","houseNumber": "241","building": "93392233"},"position": {"lat": 29.21189,"lng": 48.10424},Optimisation and Failures

Having mentioned Libpostal alone will not provide a complete conversion strategy, there are certain address scenarios you may encounter. Two common ones are covered here and through a combination of rules-based parsing, Libpostal and other functions, the code can be optimised to tackle these and provide for the best conversion success rate.

City State Addresses

In cases such as Singapore and Monaco often only one element is in the source address representing both city and country but needed in two elements in the converted address, i.e. intended as both the city and the country. This can cause issues. To solve this, the code has a separate function to specifically clone this data into city or country depending on which libpostal omits. An example for this source address:

11 Bd Albert 1er, 98000 MonacoLibpostal will parse this with city but no country, which without further improvement would fail to convert:

[('11', 'house_number'), ('bd albert 1er', 'road'), ('98000', 'postcode'), ('monaco', 'city')]The code will recognise this and clone the city to the country, using the 2-character country code, This also uses the self-contained pycountry[v] package to avoid external calls to geocoding services (geo-correction not geo-enrichment). The final address will be:

<PstlAdr>

<StrtNm>BD ALBERT 1ER</StrtNm>

<BldgNb>11</BldgNb>

<PstCd>98000</PstCd>

<TwnNm>MONACO</TwnNm>

<Ctry>MC</Ctry>

</PstlAdr>Country Names

Data quality issues suggest you may encounter a variety of names for the same country – e.g. Germany or Federal Republic of Germany. Libpostal will recognise and parse as the country, but this alone cannot produce a valid converted address. Take these three variations of the same source address:

Platz der Republik 1, 11011 Berlin, DE

Platz der Republik 1, 11011 Berlin, Germany

Platz der Republik 1, 11011 Berlin, Federal Republic of GermanyLibpostal is trained on these variations therefore recognises them and returns all 3:

[('platz der republik', 'road'), ('1', 'house_number'), ('11011', 'postcode'), ('berlin', 'city'), ('de', 'country')]

[('platz der republik', 'road'), ('1', 'house_number'), ('11011', 'postcode'), ('berlin', 'city'), ('germany', 'country')]

[('platz der republik', 'road'), ('1', 'house_number'), ('11011', 'postcode'), ('berlin', 'city'), ('federal republic of germany', 'country')]The code therefore needs to further identify any country that is not a 2-character country code and replace it (geo-correction). The final address for all three variations will be:

<PstlAdr>

<StrtNm>PLATZ DER REPUBLIK</StrtNm>

<BldgNb>1</BldgNb>

<PstCd>11011</PstCd>

<TwnNm>BERLIN</TwnNm>

<Ctry>DE</Ctry>

</PstlAdr>There are many further pitfalls and gotchas, each of which may require additional parsing and modification, none of which I would classify as geo-enrichment. In the code, even if the allow_geo_enrichment parameter is set to False, the above optimisations will still occur.

Failures and Unexpected Results

Libpostal will not fail to parse an address. It may however fail to parse the two mandatory fields, city and country. If either geo-enrichment is disallowed or it fails to find and enrich the address, once passed into stage 3, it will fail to convert to a PostalAddress24.

Far more likely is an unexpected result from Libpostal such as field concatenation. Typically, complex addresses will cause several elements to be parsed into one long element, such as road. Take this example of a business address in an industrial business park in the South of England:

Unit 2, Pulsar Business Park, Ellis Square, Selsey, Chichester PO20 0AF, GBLibpostal parses the business park name and the road, together in one element:

[('unit 2', 'house_number'), ('pulsar business park ellis square', 'road'), ('selsey', 'suburb'), ('chichester', 'city'), ('po20 0af', 'postcode'), ('gb', 'country')]The code, seeing this has both a city and town sends the address to stage 3, for conversion, and the final address is therefore:

<PstlAdr>

<StrtNm>PULSAR BUSINESS PARK ELLIS SQUARE</StrtNm>

<BldgNb>UNIT 2</BldgNb>

<PstCd>PO20 0AF</PstCd>

<TwnNm>CHICHESTER</TwnNm>

<TwnLctnNm>SELSEY</TwnLctnNm>

<Ctry>GB</Ctry>

</PstlAdr>It is this concatenation of elements that you may find problematic and is the main cause of truncation, which in turn, will cause the address to be hybrid (if allow_hybrid=True).

This type of result raises what is likely to be a recurring question. Is this converted address accurate and more importantly, good enough? In most cases, reviewing the failures is relatively easy. It is reviewing the “successful” conversions that is difficult. Often for overseas and unfamiliar countries, just identifying which element should be parsed as the building name vs street vs town vs district, can be a frustrating and lengthy process, one that is invariably manual. Ensure you plan sufficient time for this activity and have a clear definition of “good enough”. This definition should be agreed with all impacted stakeholders including compliance, financial crime, operations, data owners etc.

Stage 3. Normalise, Map and Validate

Stage 2 provides us with a parsed, corrected and possibly enriched address, as a dictionary (best_address_components). We now need to normalise and map from a defined parsed format to the defined PostalAddress24 format.

Canonical Model

The defined parsed format, or our canonical address model, is the Libpostal syntax. We have seen how various geocoders will use different syntax and without using this model, additional strategies or changing geocoders will likely require a change to the mapping.

By always parsing our source address into this Libpostal canonical model, regardless of whether a strategy uses Libpostal, we ensure this stage is agnostic of the strategy or geocoders used and has minimal dependencies on the parsing/enrichment stage.

Our canonical model, if strictly adhering to the Libpostal model, would have unnecessary elements and some omissions.

Given there is no equivalent in the target format, the following are unnecessary, and therefore not mapped:

- category

- near

- staircase

- entrance

- island

- world_region

The two omissions are department and sub department. The code does add these as extensions to the canonical model and maps them to the PostalAddress24 equivalents. Whilst a Libpostal postal strategy will not produce these, it is ready for any other strategy you may create which does parse these elements.

The complete canonical model for a parsed address and to which elements they are mapped, is shown in Figure 2.

Normalisation

The parsed address must be normalised before assessing lengths to determine truncation or hybrid options. The following normalisation is applied to each parsed element, except for the country, which by now should be a valid ISO 3166-1 alpha2 code, needing no further normalisation.

The following normalisation is applied to each parsed element, except for the country, which by now should be a valid ISO 3166-1 alpha2 code, needing no further normalisation.

Character Set Conformity

The element is checked for conformity to the CBPR+ extended character set, which applies to all address fields (in CBPR+ at least).

- Any accented characters are replaced with their non-accented equivalents (using python unicodedata).

- Any double-character symbols are replaced with two separate characters. In python, the unicodedata normalisation does not include this, hence a separate step is needed. The symbols included are below. Please adjust this code as you require:

# Unicodedata doesn't replace "œ", "æ", "ß" etc so replace first before NFKD

text = text.replace("œ", "oe")

text = text.replace("æ", "ae")

text = text.replace("ß", "ss")

text = text.replace("ij", "ij")- A final check to replace any characters present that are not permitted in the CBPR+ extended character set, using the regex below. Any found are replaced with a period “.”. Adjust the replacement character as required.

cbpr_pattern = re.compile(r"[0-9a-zA-Z/\-\?:\(\)\.,'\+ !#$%&\*=^_`\{\|\}~\";<>@\[\\\]]+")Truncation Check and Hybrid Option

The address elements are ready for mapping but each much either fit to the length of the target element, else be truncated.

To minimise truncation, if the allow_hybrid parameter is True, should any element be identified as exceeding the permitted length, it is remapped to an address_line element. As many elements could be remapped, each is appended and separated with a comma. Once all elements are checked for length, the final length of address_line is checked. If this exceeds the permitted length, it is split into 2 x address_lines. If the second instance exceeds the permitted length, it will be truncated.

The exception this this is the TownName element. This must always be present so if this value exceeds the permitted length, it is always truncated.

Any truncated field, will show this with the “+”. A hybrid example would be:

Source address:

Victoria Memorial, Queen's Way, Maidan, Kolkata, West Bengal 700071, IndiaLibpostal parsed address:

[("victoria memorial queen's way maidan", 'house'), ('kolkata', 'city'), ('west bengal', 'state'), ('700071', 'postcode'), ('india', 'country')]Final corrected and normalised hybrid address:

<PstlAdr>

<PstCd>700071</PstCd>

<TwnNm>KOLKATA</TwnNm>

<CtrySubDvsn>WEST BENGAL</CtrySubDvsn>

<Ctry>IN</Ctry>

<AdrLine>VICTORIA MEMORIAL QUEEN'S WAY MAIDAN</AdrLine>

</PstlAdr>If allow_hybrid were set to False, the result would be a structured but truncated address:

<PstlAdr>

<BldgNm>VICTORIA MEMORIAL QUEEN'S WAY MAID+</BldgNm>

<PstCd>700071</PstCd>

<TwnNm>KOLKATA</TwnNm>

<CtrySubDvsn>WEST BENGAL</CtrySubDvsn>

<Ctry>IN</Ctry>

</PstlAdr>I hope this article has shown, in sufficient detail that there are alternatives, such as Libpostal combined with other parsing methods.

The code I have made available, which forms the basis of what has been presented, should provide a template to build on. It is not production quality but does give the kick-start for the agile, rapid building, testing and constant refining of your strategies. In parallel the production integration designs can be ongoing, independently.

Validate

Once a structured or hybrid address has been produced it is validated against the relevant schema. A specific xsd for both structured and hybrid has been created and are part of the project. You will find these with the code in Github. The code simply asserts the address against these, and any errors are written to the csv output.

The code builds the xml address from these schemas and only does so if it has the required TownName and Country elements. If there is an xml address produced, it will therefore be valid. If not, it is likely a bug in the code.

Summary

Hopefully, this demonstrates an approach for converting unstructured addresses to structured and some pitfalls to avoid along the way.

Meeting the deadline, currently November 2026, may feel daunting and turning to AI LLM solutions is now becoming the default action. It may seem sensible and easy; I would argue, without careful analysis or use as a last resort, it is the lazy option.

I hope this article has shown, in sufficient detail that there are alternatives, such as Libpostal combined with other parsing methods.

The code I have made available, which forms the basis of what has been presented, should provide a template to build on. It is not production quality but does give the kick-start for the agile, rapid building, testing and constant refining of your strategies. In parallel the production integration designs can be ongoing, independently.

The key takeaways:

- Get data owners to focus on their address data quality. Fix at source.

- Build your strategies and evaluate their effectiveness then optimise and repeat.

- Clearly define and agree what a “good enough” address is.

- Separate your project into teams and methodologies to:

- Agile: to build and evaluate your strategies and identify data issues (keep it simple, agile is an enabler).

- Any methodology: to design and build the production integration of the application which your strategies will plug into.

[i] Based on Swift CBPR+ Standard Release 2025 usage guidelines for PostalAddress24 in pacs.008.001.08, pacs.009.001.08, pacs.004.001.09, pain.001.001.09 etc.

[ii] I suggest making TownName optional in the hybrid address UG would be the greatest help to banks etc struggling to be ready for November 2026.

[iii] PostalAddres24 uses the syntax Town Name (TwnNm), but we will refer to this interchangeable in this article as town or city.

[iv] The Python binding of Libpostal, parse_address takes three parameters. This may differ in the binding for other syntax.

[v] pycountry is a Python package but similar libraries are available for Java though in Java 17+ the in-built java.util.Locale will suffice.